Kotlin & Android: A Brass Tacks Experiment Wrap-Up

Doug Stevenson

Disclaimer: I am a Google employee, but the views expressed in this article are not those of my employer.

Kotlin & Android: A Brass Tacks Experiment Wrap-Up

It’s been fun exploring Kotlin® language features for use with Android development! If you’ve landed here without that context and want to explore this 7-part blog series from the beginning, you can jump back to the beginning, but there’s no need for that to understand this article.

If you have been following along with the prior 6 parts, you know that, at this point in the experiment, we have a nice domain specific language for expressing the creation of an Android view hierarchy in Kotlin. We made use of the type-safe builder pattern, along with extension functions and properties, to provide ourselves with some handy tools to make this super easy.

A question you might have at this point in the journey is this: Should I even try to use this technique to build views in my app? Up until now, I’ve only ever talked about how it can be easy and convenient to do so, but I haven’t really compared it to anything other than the same task in the Java® programming language. On that point, I definitely find that using Kotlin’s type-safe builder pattern for building views far more agreeable than the equivalent practice in Java. However, specifying views in XML resources is the standard for Android apps, so let’s break down some categories for comparison between the classic XML layouts and the Kotlin type-safe builder approach.

How well does the approach work with Activity configuration changes?

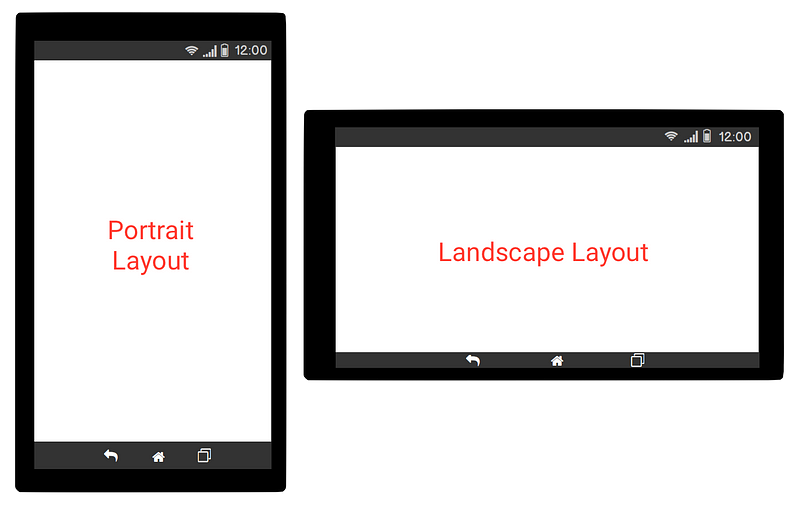

With Android, a device may change configuration at any time. The most common type of configuration change is orientation. There are many other types, as documented here (see android:configChanges within). Changes in orientation are especially important for Android views, because it is common practice to have a different layout for both landscape and portrait.

When dealing with XML layouts, it’s trivial to handle configuration changes that result in different UI. You simply define your layout twice — once for landscape under res/layout-land and once for portrait under res/layout-port. When you give the XML files the same name in these different spaces, that lets Android know to find and inflate the correct version of the layout for each circumstance. Generally speaking, you write no extra code to handle this change.

When dealing with layouts generated from code, you don’t get this configuration switching behavior for free. If you want to change layouts for different configurations, you have to write conditional logic to decide which views to create. And, if you do this a lot, it becomes cumbersome.

So, for handling a possible matrix of configuration settings with different UI, XML layouts are more convenient.

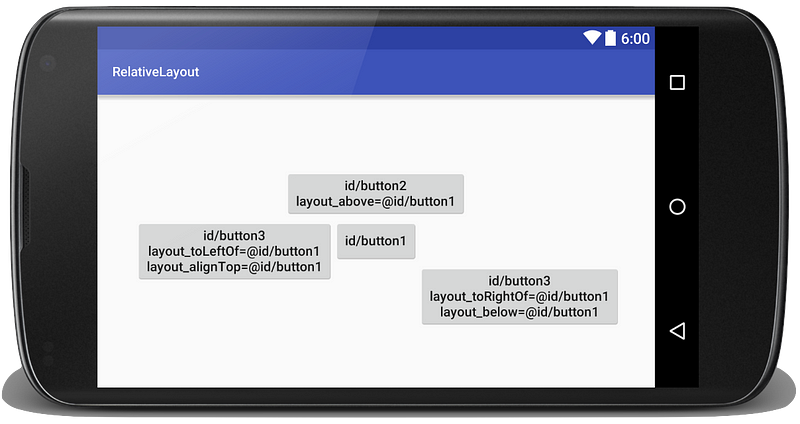

How well does the approach work for complex layouts such as RelativeLayout?

RelativeLayout is a tool that allows for a very flexible way of positioning views relative to other views. You can easily say that one view should be above, below, to the left, or to the right of another “anchor” view. This requires assigning IDs to the anchor views, while also calling out those IDs in the views to be positioned relative to its anchors. View IDs are also used to locate views within view hierarchies to make modifications to them in code.

In Android, it’s a best practice to let the compiler assign the integer values for view IDs. You shouldn’t just make up values of your own. This means that you have to use the Android tools to specify these IDs so they can be used later.

When dealing with XML layouts, it’s trivial to create a new ID. You simply call out a new value where it’s needed, usually in the view’s android:id property, like this:

<TextView android:id="@+id/tv" ... />

The +@id notation tells the Android toolchain to define a new ID called tv, or reuse an existing ID with the same name. Couldn’t be easier.

However, when dealing with layouts generated from code, it’s not possible to create a new ID in the middle of code. To create a new ID, you have to define a new ID as a resource in XML. Then you can reference it from the compiled R class that contains all the IDs used in the app. So, working with views programmatically involves dealing with another file, and Android will not automatically remove IDs for you when no longer referenced.

Considering all this, it’s easier to work with view IDs with XML layouts because of the tooling support for automatic ID management.

How well does the approach work when doing calculations to assign to attributes of views?

It’s not uncommon to want to calculate some value for an attribute of a view, such as its display text, or a background color, or its dimensions.

The Android XML layout language is purely declarative. You can’t do any computations in the strings used for assigning attributes. This means that attributes must be assigned in code later after the view has been inflated. This creates a disconnect between the definition in the layout file and its corresponding inflation code. Android programmers are not strangers to this practice!

However when building view programmatically, you can simply assign the result of a computation directly to the view property. You can also assign values to be equal to some other property on the view. How many times have you assigned the exact same value to marginLeft and marginBegin?

Given that you (of course) have all the flexibility of code when creating views programmatically, it’s definitely more convenient in this case to use programmatic view creation, especially with Kotlin type-safe builders.

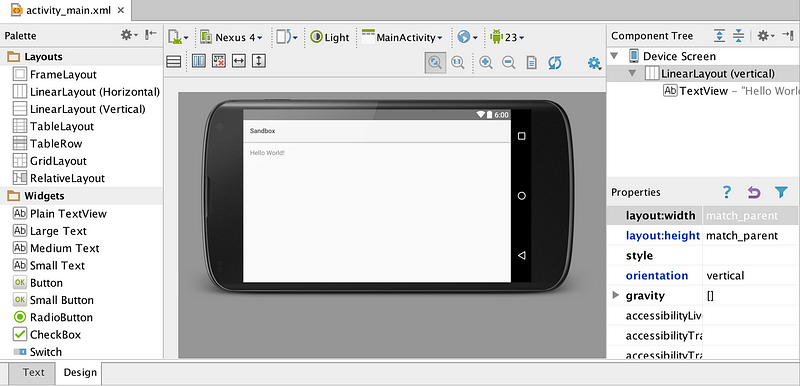

How easily can you experiment with tweaks to your layouts?

Unless you’re really good at visualizing Android layout as you write them, you’ve probably used Android Studio to preview an XML layout without having to build and deploy to a device to see the result.

When you code layouts programmatically, you don’t have a quick preview method like this. When Android Studio 2.0 with Instant Run is fully released, this situation will improve greatly. But for now, the most convenient way to experiment with layout changes is usually through the Android Studio preview pane.

What’s the performance like with each approach?

This is a matter of benchmarking inflation of a view hierarchy against equivalent code that constructs the views directly. When I first started experimenting with this, I found that building a simple layout was up to twice as fast inflation! But as I started layering in more Kotlin features and doing more complicated things with views, the difference wasn’t so stark. On my Nexus 6P, I found that building takes roughly 75% of the time it takes to inflate. Presumably, this is because inflation has the overhead of processing the layout resource as it builds the views.

It should be noted that, in either case, it takes less than 1 millisecond to end up with a view hierarchy with 5 views total, so unless you’re making a whole lot of views, performance is not a huge problem to address.

If you want to perform the benchmarks yourself, the source code to a sample project can be found in my GitHub.

What’s the size overhead of using Kotlin?

There was a dangling question from part 1 about the size requirements of using Kotlin in Android. There is a runtime and standard library for Kotlin that you declare as a compile dependency. Any time you add a dependency to an Android app, you should definitely be considering its size, especially if you’re not able to multidex your app.

With Kotlin version 1.0.0, the runtime + stdlib jars weigh in at 210KB + 636K = 846KB, which is fairly hefty for a library. Counting all the methods using dex-method-counts reveals a total of 6584 methods under the kotlin package, not including the methods in the Java runtime it also references. This is at least a full 10% of your method count budget for a single dex! But, after applying ProGuard on my test project, that number drops to just 42 methods. The final number will, of course, expand in relation to the other parts of Kotlin that the app makes use of. The bottom line is that use of ProGuard on apps that include Kotlin is crucial to keeping it under control for serious use.

Summing it all up:

Kotlin is a pleasure to use in general and can be directly applicable to Android development. For building views, it’s not a silver bullet, since there are many advantages to using XML layouts as is normally recommended. But there are definitely times when programmatic view building is preferable, and Kotlin can provide some handy shortcuts to getting that done with style.

You may also wonder what other hidden costs there are to using Kotlin. This is a valid question, and was recently addressed in a discussion on Reddit. I add my two cents to that discussion, so head over there if you want to see what some people think about that.

If you want to see my test project and compare XML layouts with views built by Kotlin, clone my kotlin-view-builder repo to easily try it out yourself.

I hope you enjoyed reading about my experiences with Kotlin for Android as much as I enjoyed learning about it myself!

I work extensively with Android, so be sure to follow me on Medium and Twitter to get my upcoming blogs.