Lessons from converting an app to 100% Kotlin

AJ AltLessons from converting an app to 100% Kotlin

I’ve been following the development of Kotlin for a while. Kotlin is a relatively new language that primarily targets the JVM, and is interoperable with Java. With the release of Kotlin version 1.0.2, which brought incremental compilation and a large reduction in the number of methods in its standard library, I was eager to start using it in production.

I’m the lead engineer on App Lock at Keepsafe, which, like most Android apps, was written in Java. There are quite a few places where Java falls short of modern languages, especially the version of Java 7 that Android supports. To reduce the pain, it is common to use libraries such as Retrolambda for a backport of lambdas and try-with-resources, Guava for immutable collections and utility functions, ButterKnife for view binding, or ReactiveX for functional programming. All of those libraries come with drawbacks, though. Retrolambda frequently causes incremental builds to fail, and every library you depend on adds methods to your APK.

Even with those libraries, Java code is verbose. Your code has to go through a lot of ceremony that the designers of Java thought was a good idea in the 90s, but is clearly unnecessary today. Kotlin provides a well thought-out syntax and extensive standard library that removes many of the pain points that exist in Java. So over the course of a few days, I converted the entire App Lock codebase into Kotlin. Here are my thoughts on the process.

Kotlin vs Java in App Lock

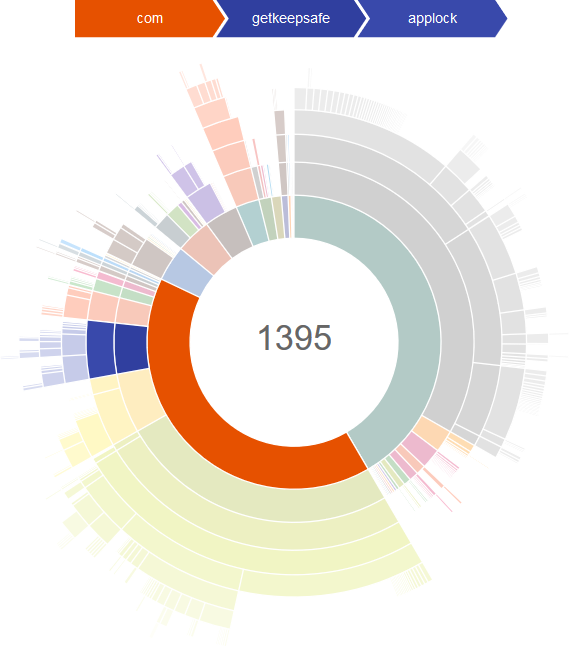

Method count in App Lock after converting to Kotlin. From the dexcount gradle plugin.

Method count in App Lock after converting to Kotlin. From the dexcount gradle plugin.

One concern that people will raise about converting to Kotlin is the number of methods added by its standard library. Thanks to massive libraries like the support library and GMS, many apps are in danger of bumping up against the Dex method limit. I used the dexcount gradle plugin to break down the method count before and after the rewrite. The end result is that the total method count after proguard decreased by 10% from 5491 to 4987 (not counting GMS or appcompat). The code count decreased by 30% from 12,371 lines of Java, to 8,564 lines of Kotlin.

Converting the app from Java to Kotlin reduced the total method count by 10%, and the total lines of code by 30%

The method count decrease is a result of both Kotlin being a more concise language, as well as the fact that many of the quality of life libraries that were previously used in Java are no longer necessary.

Retrolambda

Retrolambda generates an anonymous class for every lambda which add several methods each. Kotlin has inline methods to which a lambda can be passed without adding any extra methods.

For example, the extremely useful standard library function apply:

public inline fun nT> T.apply(block: T.() -> Unit): T {

block(); return this

}

Which is called like this:

myObject.apply **{** /* modify myObject */ **}**

Even though you’re defining a lambda function at the call site, no anonymous class is generated, so no extra methods are added, and no allocation happens due to that call. In fact, the apply function itself, like most inline functions in the Kotlin standard library, doesn’t cause a method to be added in the compiled code.

Guava

The entirety of Guava is covered by the Kotlin standard library, which has the additional advantage of being easier to use. Big Guava ComparisonChains can be replaced with a few characters with the kotlin.comparisons functions.

// Guava

ComparisonChain._start_()

.compareTrueFirst(lhs.isActive(), rhs.isActive())

.compare(lhs.lastName(), rhs.lastName())

.compare(lhs.firstName(), rhs.lastName())

.result();

//Kotlin

_compareValuesBy_(lhs, rhs,

**{it**.active**}**, **{it**._lastName_**}**, **{it**._firstName_**}**)

The null safety of Guava’s Optional class is built in to Kotlin.

// Guava

return Optional._of_(value).or(defaultValue);

// Kotlin

return value ?: defaultValue

Guava’s lazy fields and Preconditions classes are covered by the Kotlin standard library.

// Guava

private Supplier<String> lazyField = Suppliers._memoize_(

() -> "value");

public String getField() {

return lazyField.get();

}

// Kotlin

val field by _lazy_ **{** "value" **}**

// Guava

Preconditions.checkNotNull(value, "error %s", arg);

// Kotlin

_checkNotNull_(value) **{**"$arg"**}**

Nearly all of Guava’s collections classes exist in Kotlin. Even with all of that functionality, the entire Kotlin standard library is still smaller than Guava alone.

ButterKnife

ButterKnife can still be used in Kotlin, but the Kotlin Android Extensions provide a more natural way to access bound views. Other solution also exist such as Kotterknife and Anko, but I find that regular XML layouts with the Kotlin Android Extensions are currently the best way to work with Views. Kotterknife requires more boilerplate than the extensions. Anko adds thousands of methods, and its DSL is often more complicated and less capable than XML.

RxJava

RxJava is still awesome, and I still use it in many places in App Lock. But since Java on Android doesn’t have functional methods on collections, I will sometimes use RxJava as a substitute. Something like this in Java:

Observable.from(collection)

.filter(it -> it.isActive())

.map(it -> it.size())

.reduce((it, sum) -> it + sum)

.toBlocking().single();

Can be replaced with this in Kotlin:

collection.filter { it.isActive() }

.map { it.size() }

.reduce { it, sum -> it + sum }

Getting started with Kotlin

If you already know Java, learning Kotlin is easy. You can work through the Kotlin Koans online, and the reference documentation is very well written. Jake Wharton also gave a great talk about some of the useful syntax features in Kotlin.

The best part about Kotlin is that it can be called from Java, and Java can be called from Kotlin. So you don’t need to convert your entire codebase at once. I would suggest you start with a single file that you rewrite from scratch. IntelliJ has an automated Java-to-Kotlin converter, but it frequently produces incorrect code, so it’s better to start from scratch until you have a better handle on the language.

Once you have the basics down, I recommend picking some existing Java code that has few dependencies, and converting it to Kotlin. UI code like an Activity of Fragment on Android is a good place. Picking a class with no dependencies allows you to focus on just the code you’re working on without worrying about how any interfaces are changing. Keep the Kotlin reference open so that you can quickly answer questions about syntax or the standard library that come up while you’re working. You could also choose to start new Kotlin code from scratch instead of converting from Java, but I find that it’s easier to pick up some of the less obvious syntax from converted code than trying to figure it out from a blank slate. The automated conversion does a really good job in most cases, and the places where it fail are usually easy to fix.

Something to keep in mind while you’re learning Kotlin is to avoid getting overwhelmed. If you don’t already use a design pattern like MVP or MVVM, don’t worry about try to learn it at the same time. Don’t worry about finding every Kotlin library available. Just focus on taking what you know about Java and translating that knowledge to Kotlin. If you still have pain points, then you can add more libraries or design patterns.

Should you convert your entire codebase at once?

After you’ve got some Kotlin working in your codebase, you’ll have to decide whether or not to convert everything at once, or take it more slowly. Fortunately, Kotlin has excellent two-way interoperability with Java, so you can convert single classes at a time, and ship with both languages running together.

For large codebases, it can be too much work to convert everything in one release. In Keepsafe’s main app, about 15% of the code is Kotlin as of this writing. In that app, if we have to make significant changes to a Java class, we’ll usually convert the class to Kotlin while we’re working on it. This allows us to steadily improve the codebase without slowing down our work on new features.

However, if your project is small enough that you can convert to 100% Kotlin, it’s something worth considering. When you don’t have to maintain Java compatibility, you can simplify your internal APIs and remove a lot of the libraries I talked about earlier. You can convert static utility classes into extension functions, and take advantage of the stronger type inference in Kotlin.

Final thoughts

Kotlin is a great language, and is a huge improvement over Java. Converting App Lock to Kotlin resulted in an app that was faster, smaller, and which had fewer bugs than before. The language is mature enough now that there were no important features missing, in either the tooling, the language, or the standard library. If you’re wondering whether to give Kotlin a try now or if you should wait a while longer, I can tell you that Kotlin is ready for full time production use now. If you work with Android or another Java environment where Kotlin is a possibility, you owe it to yourself to give Kotlin a try.

This is the first post of a series of two. Follow Keepsafe Engineering to get notified about future posts. Interested in writing Kotlin code your self? Have a look at our Kotlin job opening.