Kotlin & Android: A Brass Tacks Experiment, Part 2.

Doug Stevenson Disclaimer: I am a Google employee, but the views expressed in this article are not those of my employer.

Disclaimer: I am a Google employee, but the views expressed in this article are not those of my employer.

Kotlin & Android: A Brass Tacks Experiment, Part 2

This is part 2 of a series exploring what the Kotlin® language can uniquely offer Android developers. Last time there was some detail on how to get Kotlin support added to an Android project. Now we’ll actually dive into code and see how some Kotlin language features can be used to do nifty things in an Android project.

When I first encountered Kotlin and pored over the list of language features, one thing in particular stood out to me. Kotlin has a feature called type-safe builders that lets you express object creation in a style that looks declarative. It allows a syntax that looks a lot like Gradle build files. But where Gradle and Groovy are dynamically typed, Kotlin is statically typed, so the compiler will let you know if you’re assigning values to properties that don’t make sense.

The typical examples of type-safe builders show how it’s possible to build nested data structures, like XML documents. When I think Android and XML, layouts and views quickly come to mind. If Kotlin is good at building up stuff like XML programmatically, perhaps it would do well with view hierarchies. So, that’s where I started. I figured I would try to create a sort of shorthand for building view hierarchies programmatically, which is code-intensive if you’re doing it in the Java® language.

Important note: I will be referring to lambdas frequently going forward. Before continuing, be sure you understand what that means in the context of computer programming, even if not specifically for Kotlin. In short, it’s a way of expressing an anonymous function that you would pass inline to another function or assign to a variable.

The core feature of Kotlin that makes type-safe builders possible is called lambda with receiver. Let’s get straight into an example that’s actually useful. Kotlin allows you to define functions outside of classes, and that’s all I’m doing here. Also note that the names of variables come before their types, which is the opposite of the Java language.

import android.content.Context

import java.lang.reflect.Constructor

inline fun <reified TV : View>

v(context: Context, init: TV.() -> Unit) : TV {

val constr = TV::class.java.getConstructor(Context::class.java)

val view = constr.newInstance(context)

view.init()

return view

}

The above function is named v for brevity as I’ll use it a lot here and in future posts, and you can call it like this:

import android.view.ViewGroup.LayoutParams

import android.view.ViewGroup.LayoutParams.WRAP_CONTENT

import android.widget.TextView

val view = v<TextView>(context) {

layoutParams = LayoutParams(WRAP_CONTENT, WRAP_CONTENT)

text = "Hello"

}

That’s equivalent to inflating an XML layout that looks like this:

<TextView

android:layout_width="wrap_content"

android:layout_height="wrap_content"

android:text="Hello" />

Neat! Now, if this is your first time seeing Kotlin, there’s a lot to translate into English! Here’s a few bits of Kotlin syntax to unpack:

The word reify means “to make an abstract thing concrete”. As a Kotlin keyword on a function’s generic type, this means that you have compile-time access to the JVM Class object specified for the generic type in the body of the function. So this bit of code says that the function v makes use of a “reified” generic type named TV (think “Type of View”) which must be View or a subclass of View. The function must also be declared inline for this to work. The caller then gives TV a specific type in angle brackets when calling the function.

init: TV.() -> Unit

v takes two parameters, a Context and a lambda named init. init is special because it’s a lambda with receiver type function reference. A lambda with receiver is a block of code that requires an object of a certain type. This required object is referenced by the keyword “this” in the body of the lambda. The type of the receiver object here is the reified generic type TV.

In our specific case, function v is declaring, “I’m going to create an object of type TV, and I need you to tell me how to initialize it”. So this new TV type object becomes the receiver of the provided lambda, and the lambda is invoked by v with view.init() so it can perform some actions with the view. The “-> Unit” in the syntax is just saying that the lambda returns type Unit, which is like the type void in Java code. In other words, it returns nothing.

To summarize this lambda with receiver:

- v declares a parameter called init which is a lambda with receiver for type TV.

- v creates and initializes a TV type object and invokes the lambda on it to initialize it.

- The lambda sees the TV type object as “this” in its chunk of code.

TV::class.java

To reference the reified generic type TV’s implicitly available Class object in the function, you can use the expression TV::class.java. This kind of expression is a very special Kotlin feature for reified generic types that drastically reduces the amount of code you must write in functionally equivalent Java code.

At this point, I’m going to anticipate a couple more questions you might have about this function:

“Why does v take two arguments, but appear to be given only one inside the argument parenthesis?”

This is another unfamiliar syntax to Java programmers. In the Java language, all the arguments to a function always appear inside the call’s parentheses, which can be a lot of added lines if it includes an anonymous callback. But in Kotlin, there is a special syntax when a lambda is the last argument to a function. This syntax allows the lambda to appear in curly braces immediately following the parentheses of the function call. You could put the whole thing inside the parentheses, but most of the time it’s neater this way and keeps the function call parentheses on the same line, so they’re easier to track. Also, this lambda syntax is similarly available when inlining anonymous Java objects that have a single method, such as Runnable.

“Are ‘layoutParams’ and ‘text’ some sort of variables?”

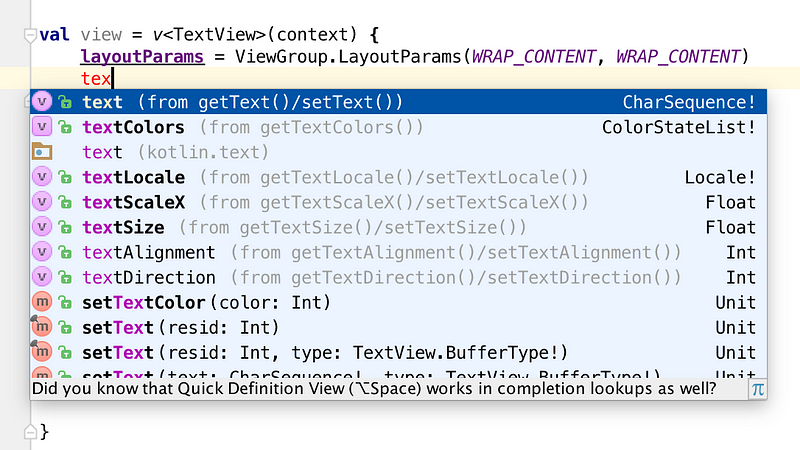

A syntax feature of a lambda with receiver is that the “this” keyword may be omitted when referencing methods and properties of “this” inside the lambda. But what exactly are layoutParams and text in the call example? These are provided by Kotlin as properties of the receiver type TV (a TextView in our example). Because TextView has methods for setLayoutParams() and setText(), Kotlin recognizes those as JavaBeans-style accessors and creates properties for them that can be accessed as if they were Java class members. So, text = “Hello” here is exactly equivalent to this.setText(“Hello”). Slick! Here’s a screenshot of Android Studio with the Kotlin plugin showing specifically what’s going on during autocomplete:

As you can see, the Kotlin plugin is pointing out to us that the property called “text” (among other properties) is derived from the underlying JavaBeans-style getter and setter methods of the TextView type receiver object.

“What is this Constructor business? Can’t we just say “new TV(context)”?”

Since the compiler doesn’t know exactly what a TV is yet in the method body of v, we can’t instantiate it using new + classname. However, we can use the reified class object (TV::class.java) to locate a Constructor that takes a Context as the single argument. It’s conventional for Android View types to have a constructor with this signature, and we’re depending on it. This Constructor object can be invoked to get a new instance of type TV, with the same effect as the new keyword in Java code. This is a reasonable price to pay for the flexibility of having a single function work for all types of views instead of creating a whole new function for each type of view you want to build. And we can optimize this a bit more later in a future part to this blog series.

That’s a whole lot of convenience for a few lines of code! If you’re new to Kotlin, you might want to go back and digest this a second time, because some of these concepts can be very foreign to Java programmers. It certainly took me a bit of studying to grok all this new stuff.

This is just the beginning of my experiment. There’s still many ways this function could be enhanced and made easier to use. For example, it would be great if we could build entire nested view hierarchies in a single expression. So stay tuned for the next post in this series to see how we can use Kotlin to do that!